In early June, eight undergraduates arrived at UMBC for the first edition of SCIART. The unique summer fellowship program funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation seeks to “continue to develop the students’ science expertise while also developing their appreciation for the arts and humanities,” says Zeev Rosenzweig, UMBC chemistry and biochemistry chair, who spearheaded SCIART.

Interdisciplinary programs like SCIART prepare students for a widening range of possible career paths, helping to address the challenges and opportunities presented by an evolving career landscape that emphasizes teamwork and creative problem-solving.

SCIART students work on scientific research projects under the guidance of faculty from UMBC and Johns Hopkins University. Each project has a specific art conservation application at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, and museum staff collaborate closely with UMBC to run the program. “I’m so thankful to my colleagues here at UMBC and our partners at Johns Hopkins and the Walters,” Rosenzweig says. “SCIART would not be possible without their commitment to the program, and more importantly, to the students.”

Students make frequent field trips to the Walters. The program also includes visits to the conservation science laboratories of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC; New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art; the Winterthur Museum, Garden, and Library in Delaware; and the Library of Congress. The trips give students the opportunity to interact with conservators, conservation scientists, curators, and other museum professionals whose careers blur the boundaries between art and science.

“One of the best parts has been getting to work with people in the conservation community who have so much experience,” says Marie Desrochers, an art history major with a chemistry minor at the University of Central Arkansas. Before arriving, Desrochers already planned to pursue graduate study in art conservation. “I really love art,” she says, and as a conservator, “You get to be the person that goes behind the scenes and gets the most intimate experience with the objects.”

Janaya Slaughter, a chemistry major at Stevenson University, was planning on pursuing a master’s degree in forensic science. This summer, however, opened her eyes to how much science is involved in art conservation. “Every time we go on a museum trip I get more excited,” she says.

Feddi Roth, a rising sophomore at Stanford University, is still undecided on her major, but she is interested in chemistry and loved her first art history class. She knew SCIART would be the perfect summer opportunity. Now she’s “definitely thinking of art conservation as more of a career option.”

Julie Lauffenburger, director of conservation and technical research at the Walters, discussed with the students how the path to a conservation science career is still not clear-cut. “That’s why this is such an important program,” she explains.

SCIART is also an opportunity to work in a team of peers with varied expertise. Slaughter, Roth, and Khalid Elawad, a materials science major at Johns Hopkins University, are investigating how vibrations from music during events at the museum may affect the structural integrity of art nearby. They needed an abundance of physics knowledge, learned new software programs, and even wrote their own code to analyze data. None of them had any programming experience before SCIART.

“The learning curve was the biggest challenge,” says Elawad, but the team rose to the occasion. In the end, “We all walked away with skills that we never thought we would have,” he adds.

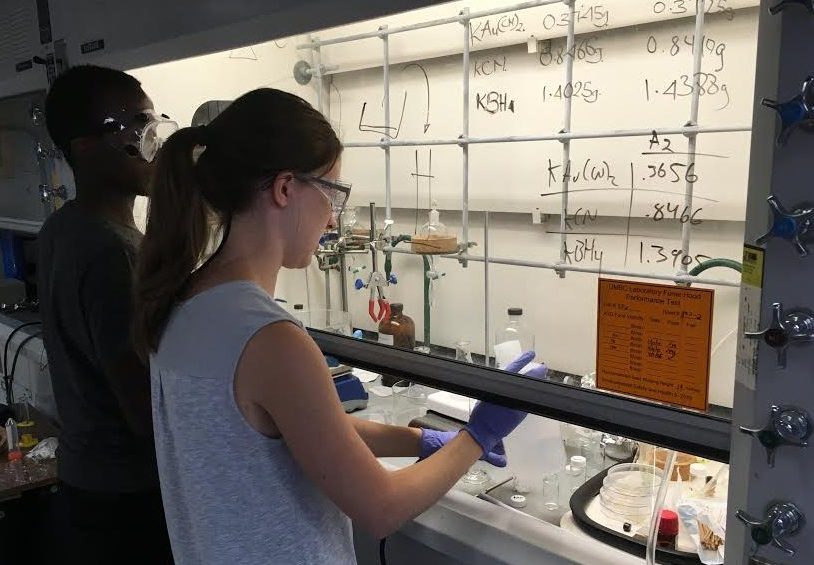

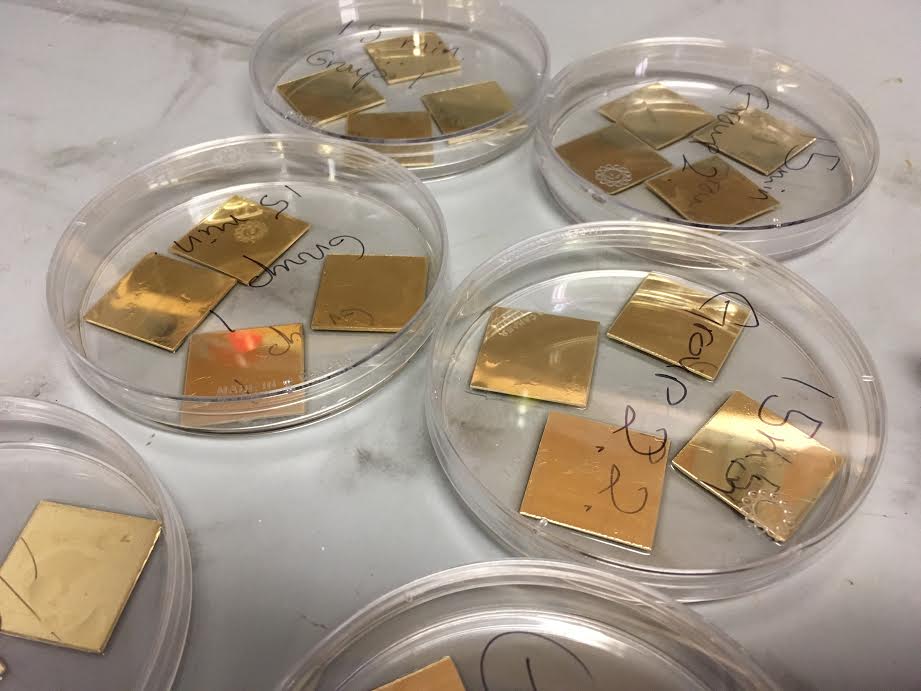

Alex Taylor, a chemistry and archaeology double major at Johns Hopkins, and Sam Maina, who studies biology at UMBC, are working with Desrochers to analyze the effects of different cleaning methods on ancient objects. This team, too, faced its challenges, but the end goal is more than answering a scientific question. “It’s about bringing together people from different disciplines to problem solve,” Desrochers says.

Alex Taylor, a chemistry and archaeology double major at Johns Hopkins, and Sam Maina, who studies biology at UMBC, are working with Desrochers to analyze the effects of different cleaning methods on ancient objects. This team, too, faced its challenges, but the end goal is more than answering a scientific question. “It’s about bringing together people from different disciplines to problem solve,” Desrochers says.

Part of what makes SCIART unique is that the students get to work on real problems. Terry Weisser, Lauffenberger’s predecessor at the Walters, told the students, “What you’re doing here has potential to be really important in the field.” High expectations make the experience that much richer for students. “It’s easy to stay motivated when you know you’re really going to help somebody,” shares Elawad.

A few students may be offered extended fellowships to continue work with the Walters after the summer program concludes. All students, however, will come away with their eyes open to the possibilities for interdisciplinary careers and the team-building and problem-solving experience they need to succeed.

For more information about SCIART and how to apply, click here.

Header: Students tour the conservation labs at the Walters Art Museum; photo Jason Putsché. Top image: Sam Maina (l) and Marie Desrochers (r) work in the lab. Bottom image: Gold-plated “coupons” on which Maina, Desrochers, and Taylor will test cleaning techniques. Photos by Sarah Hansen.

Tags: CAHSS, ChemBiochem, CNMS, Research, Undergraduate Research, VisualArts